Prehistory is often overlooked—no kings, no scrolls, just stones and bones—and people tend to press "skip" right to shiny diorite statues of Ancient Egypt or clay-bricked ziggurats of Mesopotamia. I consider it a staple; understanding this era is essential to understand ourselves as a species. In this piece, I’ll outline core bits that will finally close the knowledge gap on prehistory for you and me—unless you’d want to go deeper. 😉

Studying prehistory is getting the ultimate origin story—it shows us how we, as humans, evolved, adapted, and innovated long before we had written records. It helps us understand what happened from our early survival skills to the spark of creativity that led to agriculture and even art.

Knowing our roots gives us perspective on who we are today, and it’s just fascinating to see how far we’ve come.

Now, 3,000,000 years is a vast amount of time to get through! If we’d agree to match this reading to under 30 minutes, that would be a tempo of 100,000 years per minute. Isn’t that a time-travel experience? 😉

The thing is, though, if we wanted to, we could manage to tell the story in under 3 seconds—here you go:

Prehistory marks the era—from roughly 3.4 million years ago—when early humans evolved, harnessed fire, developed speech and tools, and laid the foundations for the first written records in Mesopotamia.

For some, that would be more than enough, and it is okay.

If there’s more you wish to know, in this article you’ll learn what prehistory is and who studies it, its massive timeline, key milestones like fire and farming, evolution from early hominins to us, Stone Age basics, and a cultural snapshot showing they weren’t so primitive.

You won’t get a comprehensive overview by any means, but it will be SUFFICIENT, as in "enough to say I know prehistory"—this I promise.

A Looong Time Ago

Here is a photo of some really old bones, take a look:

Dikika research project

See anything interesting? Upper bone, upper left corner? Let me help you:

Dikika research project

Those etched lines are the oldest known evidence of stone tool use by early human relatives, made some 3.4 million years ago.

Numbers like that are hard to process for our brains, so imagine a nice, minimalistic clock where each minute is worth 100 years:

By this clock voyages to the Americas began only 5 minutes ago. Twenty minutes ago, Christianity appeared. Around an hour ago, southern Mesopotamia received its first inhabitants, soon to evolve into the first civilization known to us. This is already where the border of written records—of history—ends.

According to this clock, our etchings were made around 23 days, 14 hours, and 23 minutes ago. Ironically, they mark not only bones but the beginning of the period we call prehistoric.

This Isn’t History

Prehistory simply means "the human story before writing began."

That’s why we pay so much attention to those 3.4-million-year-old marks: to understand the borders of the period, we need to know as precisely as possible when they were made.

I generously use "we" as in "we humans," but really, there’s just a handful of people so interested in prehistory that they spend their lives studying it. A round of applause for archaeologists!

Yeah, just like that, years of accurate meticulous digging and meters of earth. Image source: https://phys.org/news/2019-07-archaeology-student-unusual-peruvian.html

These guys dig up artefacts (or, put simply, objects made by humans like tools, paintings, and bones)—like a chipped tool or a fading cave painting—on ancient sites and draw conclusions.

Besides archaeologists, quite a few other pros round out the picture: paleoanthropologists track our evolution from early ancestors to us, geologists read the earth’s layers like a history book, spotting floods or eruptions that shaped human life, and climatologists decode ancient weather to explain why some groups thrived while others faded. A whole squad chips in—fossil hunters, plant buffs, you name it—to crack the prehistoric code. Trying to figure out what happened in the past requires real teamwork.

Keep in mind, though, that despite all their efforts, there are still no names and no dates. That’s why it’s called prehistory—we only have a rough idea of when it all happened 🤷♂

Old, Middle, New

You don’t expect all 3 million years to pass just for people to start doing all kinds of stuff out of nowhere, do you?

When written history begins, people already had everything we do today: tools, houses, farming, dogs, weapons. But despite having all these items, there had to be a starting point.

Someone had to discover them.

It’s incredible.

But do you know what else these cavemen invented? Talking.

Real conversations with each other, using words. Animals make noises too—they can cry out when they feel pain and make warning calls when danger threatens—but they don’t have names for things as human beings do. And prehistoric people were the first creatures to do so.

Image Source: https://www.jpost.com/archaeology/article-733442

It all happened during prehistory, but since there are no dates, scientists use material evidence—like tools, art, and remains—to mark shifts in human development. They help us organize and understand how technology, culture, and environment changed over time.

Let’s take a look at a general timeline before diving right in:

3,400,000 BCE - 10,000 BCE, Old Stone Age, or the time of hunter-gatherers.

10,000 BCE - 8,000 BCE, Middle Stone Age, a transitional period with refined tools and adaptations.

8,000 BCE - 4,500 BCE, New Stone Age, the advent of agriculture, permanent settlements, and more sophisticated tool-making.

4,500 BCE - 3,000 BCE, Copper Age, a transitional period before the Bronze Age where early societies began using copper tools and write.

Sorry for the scale though

People often refer to these ages by their fancy names that come from Ancient Greek. Λίθος (líthos) means “stone,” complemented by:

Paleo- comes from palaios, meaning “old.”

Meso- comes from mesos, meaning “middle.”

Neo- comes from neos, meaning “new.”

Chalco- comes from chalkos, meaning “copper” (or ore).

Simple, right?

Perhaps you’ve seen some slightly different dates for this timeline. That doesn’t mean this or that source is inaccurate—please remember, we’re talking about times when literally nothing is clear, so approximations are made.

I’ll share mine so you’re aware of what I’m getting you into: dates intersect and overlap heavily, and different periods ended at different times depending on the region. In one place, people might be working with copper, while another is still deeply stuck with stone tools. The modern world has such examples too; just think of some Polynesian or African tribes.

That’s not comfortable for telling a story, so I’ve streamlined things a bit for its sake. 🤗

Old Stone Age

Remember the magic clock and how prehistory started 23 days, 14 hours, and 23 minutes ago?

The Paleolithic period takes up 23 days and 7 hours out of them.

Yeah, things were reeeeeeallly slow those days—not much was happening for hundreds of thousands of years at times! However slow on the surface, it was brewing beneath some of the greatest inventions of all time and a fascinating story of the evolution of our own kind.

The Old Stone Age is divided further into Lower, Middle, and Upper Paleolithic. They break down this vast period into more manageable chunks, marking shifts in technology, culture, and us humans.

Lower Paleolithic (3M - 300k years ago)

How to better describe what the world was like during the Lower Paleolithic? 🤔

A rollercoaster of extremes. Changes in Earth’s orbit caused the climate to swing back and forth between cold, dry glacial periods and warmer, wetter interglacial periods. Ice ages flipped to warm spells. Surely, the changes weren’t abrupt—they unfolded over many millennia—but they deeply influenced the landscapes and habitats of early humans.

Photo by Birger Strahl on Unsplash

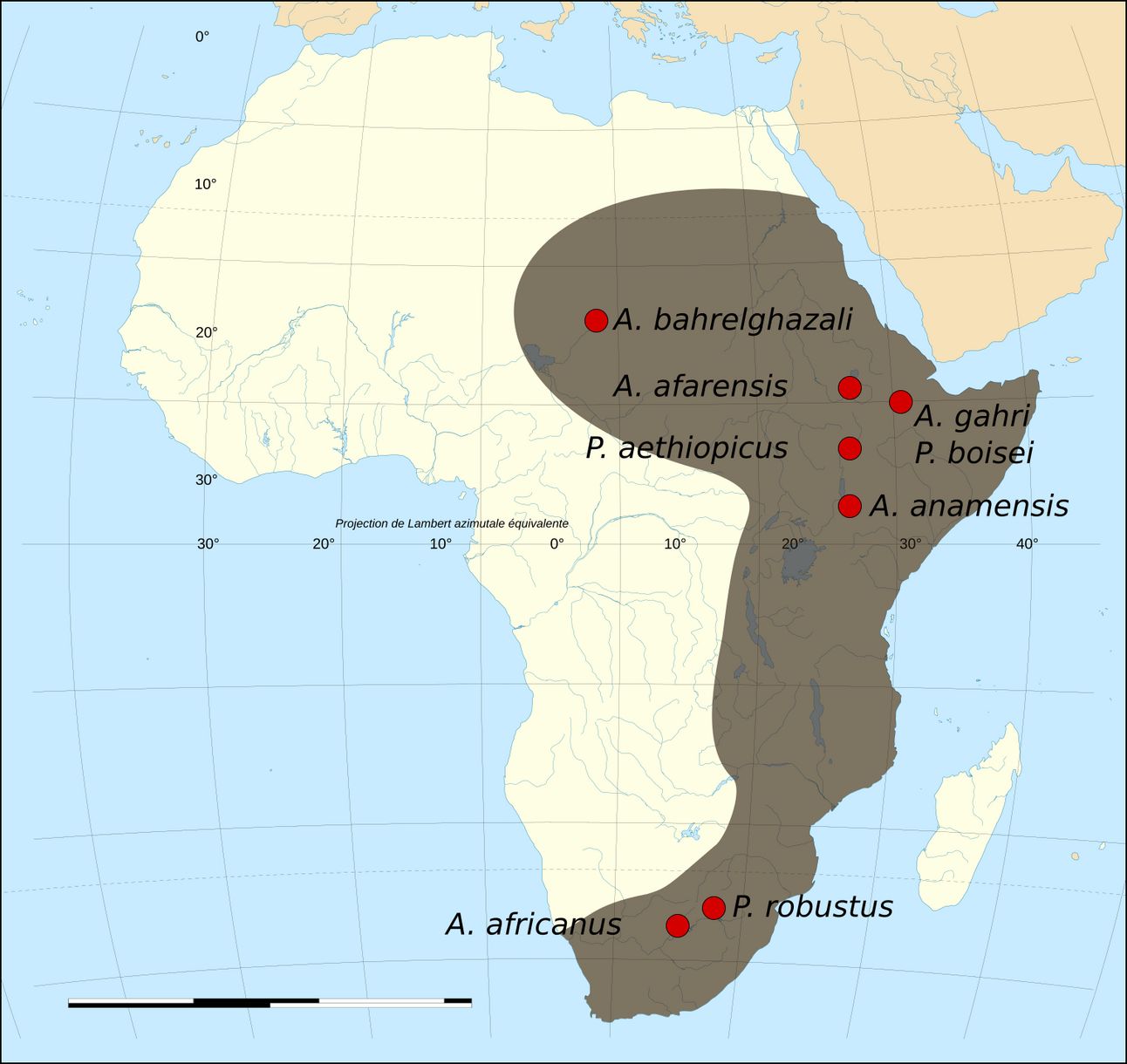

Should we then be surprised that we, as a species, began our way in Africa, the single best-conditioned zone to incubate life?

Fossils map, courtesy of http://www.archaeologyinfo.com/species.htm

Australopithecus

Speaking of Africa—there’s someone you need to meet. Imagine a creature around 1 to 1.5 meters tall with a sturdy, compact build. They walked upright and had long, curved arms for climbing trees. Their faces had a bit of a forward jut.

This creature is our early ancestor, a kind of mix between ape and human, called Australopithecus (pronounced os-TRA-lə-pi-THEE-kəs; from Latin australis, “southern,” and Ancient Greek πίθηκος (pithekos), “ape”).

A sculptor's rendering of "Lucy," Australopithecus afarensis, at the Houston Museum of Natural Science on August 28, 2007. Dave Einsel / Getty Images

They lived in small groups, roamed savannas, and used tools to get food. They were the first bipedal creatures, meaning they walked upright on two legs. These folks set the stage for our ancestors—the whole Homo genus down the road—by interacting with the environment in a fundamentally new way.

By the way it was Lucy’s folks who left the marks on the bones you saw at the very beginning!

Homo habilis

Now imagine a step up from Australopithecus: about 1.3 meters tall, 32-45 kg in weight—you’d get Homo habilis, whose name means “handy man.”

This creature, emerging around 2.4 million years ago, was a bit taller and sported a slightly larger brain than its Australopithecine relatives. Picture someone with a more human-like face and smaller teeth, but still pretty rough around the edges compared to us.

Homo habilis got its nickname because it was really good at using tools. They started making more refined stone tools—what we call Oldowan, named after Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania where these were first discovered—which allowed them to better butcher animals and work with plants. Their hands were getting smarter too—more dexterous—making it easier to create these tools and use them to solve everyday problems.

Like Australopithecus, Homo habilis likely lived in small groups, foraging and scavenging in their environment. But with these new tools, they could tackle challenges in ways their predecessors couldn’t. They represent the early spark of what it means to be “handy”—a crucial milestone on the long road from our early, ape-like ancestors to the sophisticated beings we are today.

A diorama at the Nairobi National Museum portrays early hominins processing game with tools.

Homo erectus

Next, around 1.8 million years ago, comes a real game-changer—Homo erectus; “erect” means upright. Standing 1.6 to 1.8 meters tall, they were taller and leaner than Homo habilis and definitely looked much more like you and me.

These guys leveled up their tool-making game.

Acheulean tools collection. Image source: https://becominghuman.org/timeline/earliest-acheulean-tools/

They crafted more refined Acheulean tools (named after the Saint-Acheul site in France where they were found)—think hand axes and cleavers that required planning and skill. Their tools weren’t just for chopping meat; they were used for processing plants and even building shelters. And here’s the kicker:

Homo erectus was among the first to master fire ~1M years ago.

I don’t know whether Prometheus took part in that, but imagine the impact—fire meant warmth, protection, and the ability to cook food. Cooking not only made meals tastier but also unlocked more nutrition, giving them the energy to explore new ideas and environments.

Their pattern of living was rather familiar—small, wandering groups—but their outstanding ability to adapt made it possible to spread out of Africa, for they could thrive in a variety of different climates and landscapes.

This combination of improved tools, fire mastery, and adaptability really set the stage for everything that came later. Homo erectus wasn’t just surviving; they were experimenting with new ways to live and interact with the world. They showed us that being upright and resourceful could open up a whole new chapter in evolution, paving the way for more complex social structures and even bigger brains down the line.

Homo erectus represents a significant leap toward modern humans—a link between the simple, early tool users like Homo habilis and the sophisticated species we eventually became.

Middle Paleolithic (300k - 50k years ago)

Finally, after 1,500,000 years of a total wild-ride climate-wise, we appeared!

Well, not exactly we as complete modern humans, but very close.

Homo sapiens emerged 300,000 years ago in Africa, marking the new period of the Old Stone Age called the Middle Paleolithic, and spread across the globe. This time, the change wasn’t just about physical appearance—the leap in brain size led to incredible advancements in thinking, creativity, and communication.

Bigger brains meant smarter people, which meant cooler tools and sophisticated techniques for shaping stone, wood, and bone—simple hand axes and cleavers got an upgrade and served much better for hunting, gathering, and crafting.

Tools example, pinterest.com/smithsonian/

It’s more than that—this period also marked the dawn of art. Researchers have discovered engraved bones, shells with mysterious decorations, and pieces of ochre with deliberate markings. These artefacts suggest that, even in a time dominated by survival, early humans began to express dreams, not just dinner.

Venus of Tan-Tan, oldest sculpture. Creepy, but humanity will get better. Image: https://www.maghrebmagazine.com/tan-tans-oldest-human-sculpture-in-the-world

Perhaps the greatest of their inventions—standing on par with the fire invented by their ancestors—was language. Now they could live in larger, organized groups where communication was key. It allowed them to share ideas, pass on knowledge, and build the cultural foundation of a community.

Here’s another interesting piece: when Homo sapiens showed up, they weren’t the only species. There were Neanderthals (named after a place in Germany where a skull of this species was first found)—who were pretty tough and well-adapted to the chilly climates of Europe back then.

Neanderthals were excellent hunters with a strong, stocky build and had lived in those regions for a long time. Strong as apes, they were much stronger than us. But when modern humans arrived, things started to change. Homo sapiens had sharper minds, better communication, and more creative ways of using tools and art, which gave them an edge in competing for resources.

Another Neanderthal image, but I lost the source :(

There’s evidence that these two groups even interbred a bit, but ultimately, our ancestors outcompeted the Neanderthals. Over time, as Homo sapiens spread across Europe and Asia, they gradually became the dominant group, and Neanderthals eventually faded away, making Homo sapiens the only inheritors of the future.

Upper Paleolithic (50,000 - 10,000 years ago)

Cold, sunny day. A giant, hairy mammoth, its right leg pierced by a spear, staggers and cries out in pain. It races through thin trees toward an icy dead-end. Behind, a band of strange, hairless hunters shout with wild intensity, their voices echoing through the open space. There’s no escape—only a colossal, ice-covered hill wall that no beast of its size could scale. In that desperate moment, the chase ends. Coordinated efforts, honed by generations of struggle against the elements, prevailed this time. Welcome to the epoch of the iconic mammoth hunt.

"Mammoth Hunters" by Ernest Griset.

The Upper Paleolithic was a wild, dramatic rollercoaster ride in human history, spanning roughly from 50,000 to 10,000 years ago. At the start, around 50,000 years ago, our ancestors were living in a world gripped by a glacial period. The climate was harsh and icy—northern regions were buried under vast ice sheets, and survival depended on mastering cold conditions.

Early humans used advanced tools that were more refined than anything before. Composite tools—meaning tools blending wood, bone, and sharp blades—emerged. Hunting techniques became more organized and efficient, allowing for even larger communities to exist. Daily conditions improved big-time!

Example of composite tools, taken from https://pinterest.com/linghunt/

Fast forward to around 20,000 years ago, the world reached the Last Glacial Maximum—a peak in the glacial period when ice sheets were at their largest. Everything was even colder, and resources scarcer. But then, around 14,000 years ago, the climate began to warm. As the ice melted, the environment transformed dramatically. With the warming came more fertile lands and new opportunities. In these interglacial periods, the harshness of winter softened, giving way to milder conditions that allowed nature to flourish and, importantly, freed our ancestors to focus on more than just survival.

This warming phase sparked a burst of creativity among early humans. With a bit more breathing room, people began to experiment with art and symbolism. Cave walls across Europe—like those at Lascaux and Chauvet—became canvases for stunning paintings and carvings.

Besides paintings we've found carvings and symbolic objects giving us a hint for rich inner life of storties, rituals, or may be even rearly forms of religion.

By the time we near the end of the Upper Paleolithic—around 10,000 years ago—the dramatic swings between glacial and interglacial conditions had set the stage for a whole new era. Hunts and art primed our ancestors for farming. They had evolved from mere survivors into innovators, capable of complex thought and creative expression. This legacy paved the way for the Neolithic Revolution and the dawn of settled, agricultural life.

From the frozen challenges of 50,000 years ago through the harsh Last Glacial Maximum at 20,000 years ago to the creative warmth of the interglacial phase beginning around 14,000 years ago, the Upper Paleolithic was a time of incredible adaptability and innovation—a period when early humans truly began to thrive and leave a lasting mark on the world.

Recap

We've just made a journey from 3.4 millions years ago to just 10.000 BC. How does it feel? I know, still to much information, so here is a little recap for your reference.

Prehistory—3.4 million years of humans clawing their way from Africa’s savannas to every corner of the globe. It kicks off with Australopithecus, those sturdy little ape-human hybrids leaving tool marks on bones, and rolls through Homo habilis’ handy stone choppers to Homo erectus taming fire and fanning out. Then, 300,000 years ago, Homo sapiens crash the party with bigger brains, sharper tools, and the gift of gab—outsmarting Neanderthals and painting caves by the Upper Paleolithic’s end. From icy mammoth hunts to the first whispers of art, it’s a slow-burn saga of evolution, survival, and ingenuity, all before a single word was scribbled down.

Zoom out on our magic clock: the Paleolithic’s 23 days of stone tools and fire mastery dwarf the Mesolithic’s fleeting minutes and the Neolithic’s late bloom of farming and settlements. It’s a rollercoaster—glacial chills, warm spells, and a parade of game-changers like bipedalism, language, and cave galleries at Lascaux. Prehistoric folks weren’t just grunting cavemen; they lived in groups, adapted like champs, and laid the cultural roots for everything we take for granted.

That’s the gist—enough to say you know prehistory’s wild, sprawling tale, unless you’re itching to dig deeper.

After the Ice

It’s like we can almost glimpse those metaphorical Mesopotamian ziggurats on the horizon, with the familiar shapes of history looming just behind…

Hold up—we’re not there yet! There’s more to unpack before we step onto written ground: the Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Chalcolithic periods.

Stay tuned for Part II, coming in a few more articles!

And if you can’t wait to tackle prehistory yourself, check out in the meantime my article on how to study history in a fun, efficient way in under 10 minutes.

I am Rick, and I write pieces on Ancient History and related topics as I progress towards my PhD in 10 years starting from zero 🚀