You have a plan, a plane ticket, and a booked excursion to some fascinatingly ancient site, and a few weeks later, you're standing right in front of what you've only seen in internet pictures.

However, the Wikipedia knowledge you've grasped on the way there doesn't quite hold up to the moment; both the "English" and the "guide" turn out to be exaggerations, leaving you staring at old stone blocks with awe in your eyes but still there is a monkey playing cymbals in your head.

"What the heck am I supposed to do now?"

It takes a little effort to appreciate a piece of art or a classic musical composition, and the same is true for ruins.

In this article, I'll introduce you to some pieces of geology through the examples of 11 essential stones that ancient civilizations used in their daily life, so you can see much deeper into the past than your color-shirted excursion peers.

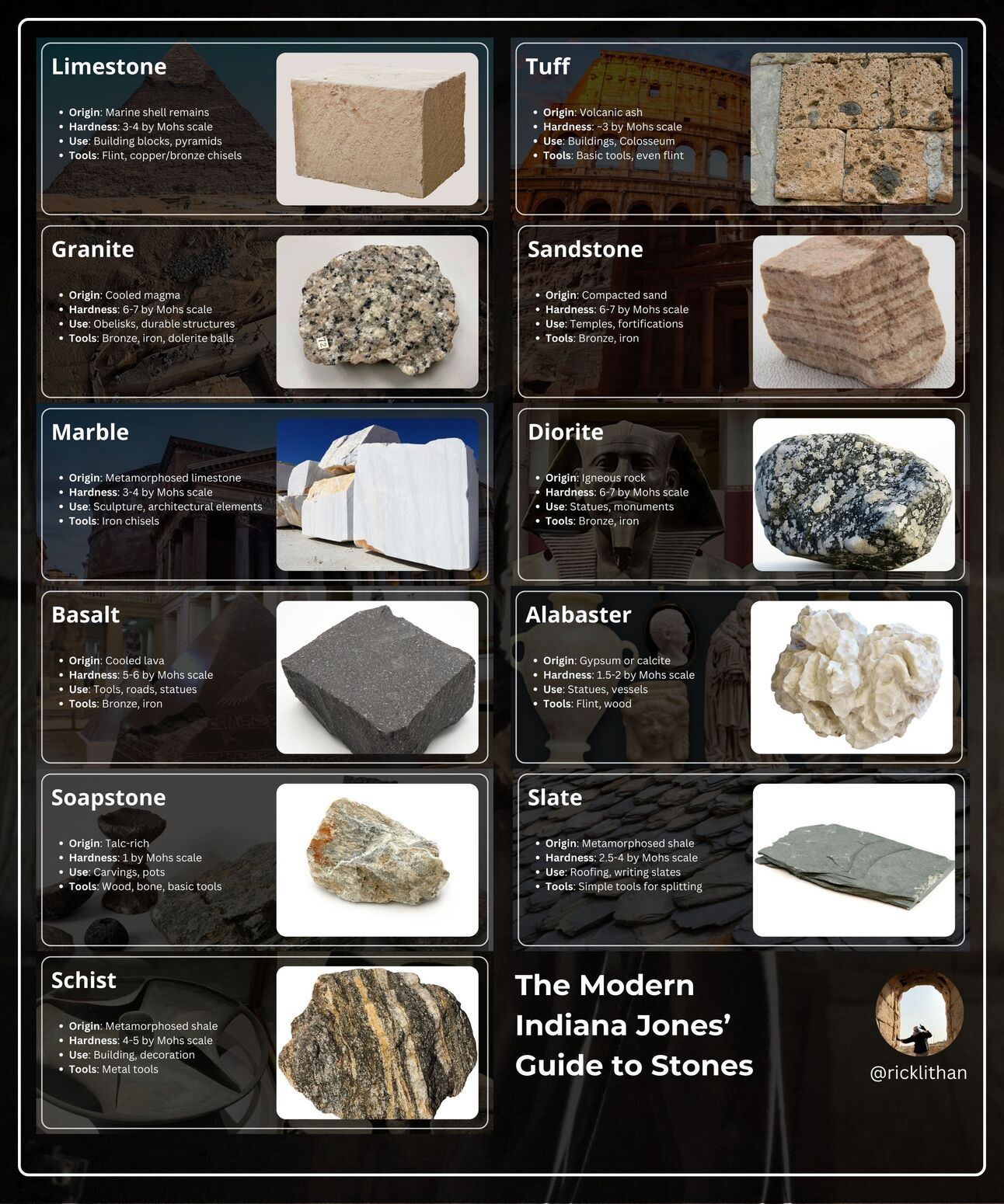

The Stones

While there are thousands of types of stone that have been quarried through centuries all around the world, it is just a handful that we can call ubiquitous in Ancient World:

Limestone: (very abundant; structures & reliefs)

Marble: (elegant; certain arch elements like friezes/pillars & sculptures)

Sandstone: (durable; used in temples & forts)

Granite: (hard & durable; obelisks & monuments)

Basalt: (strong; used for tools & roads)

Alabaster: (soft; ideal for carvings & vessels)

Schist: (layered; for building & decoration)

Diorite: (tough; statues & enduring structures)

Tuff: (light; ancient buildings like Colosseum)

Slate: (flat & tough; roofs & writing surfaces)

Soapstone (Steatite): (very soft; carvings & cooking pots)

💁♂ If this list scared you, don’t worry, for I won't bother you with detailed excerpts from geology encyclopaedias. You won’t need pen and paper neither, I’ll give you a pack of flashcards by the end of this article to keep as a ref. During reading, try to recollect if you have any memory of a certain stone in your experience. That would be more than enough for the information to stick.

Foundational Stones

Available, easy to work with, strong for foundational or extensive construction work.

Limestone

Limestone Meta card

🟢 Origin: A rock formed from layers of ancient sea creatures' shells and other ocean materials, mainly made from a mineral called calcite.

🪨 Category: Sedimentary.

💪 Hardness: Rated between 3 and 4 on the Mohs scale, limestone is relatively soft and easy to work. Its hardness can vary based on composition, porosity, and the presence of fractures.

⚒ Tools for Working: Can be shaped with flint tools for basic work, but copper or bronze chisels offer better efficiency, with iron chisels being ideal for finer carving.

🌦 Weathering: Limestone weathers quickly due to its reactivity with acids, particularly from rainwater, leading to phenomena like karst landscapes and the degradation of limestone structures over time.

🏗 Historical Use: Due to its abundance, limestone has been extensively used by numerous ancient civilizations:

Greece: For structures like the Parthenon.

Rome: In buildings like the Colosseum and in infrastructure like aqueducts.

Maya, Aztec, Incan: For constructing pyramids, temples, and other monumental architecture.

Assyrian, Babylonian, Hittite: In ziggurats and relief carvings.

Phoenician: In city constructions.

Egypt: Most notably in the Great Pyramid of Giza, where it was used both for the core and the original fine white limestone casing.

Sandstone

Sandstone Meta card

🟢 Origin: A rock formed from compacted sand grains, stuck together by natural glues like silica, calcium carbonate, or iron oxide.

🪨 Category: Sedimentary.

💪 Hardness: Varies but typically around 6 to 7 on the Mohs scale due to quartz content.

⚒ Tools for Working: Requires harder tools like bronze or iron for effective shaping. Flint might be used for softer varieties.

🌦 Weathering: Resistant to weathering due to its composition but can erode over time, especially in sandy or windy environments.

🏗 Historical Use: Used by the Egyptians in building projects, by Romans for fortifications, and in various structures throughout history due to its availability and workability.

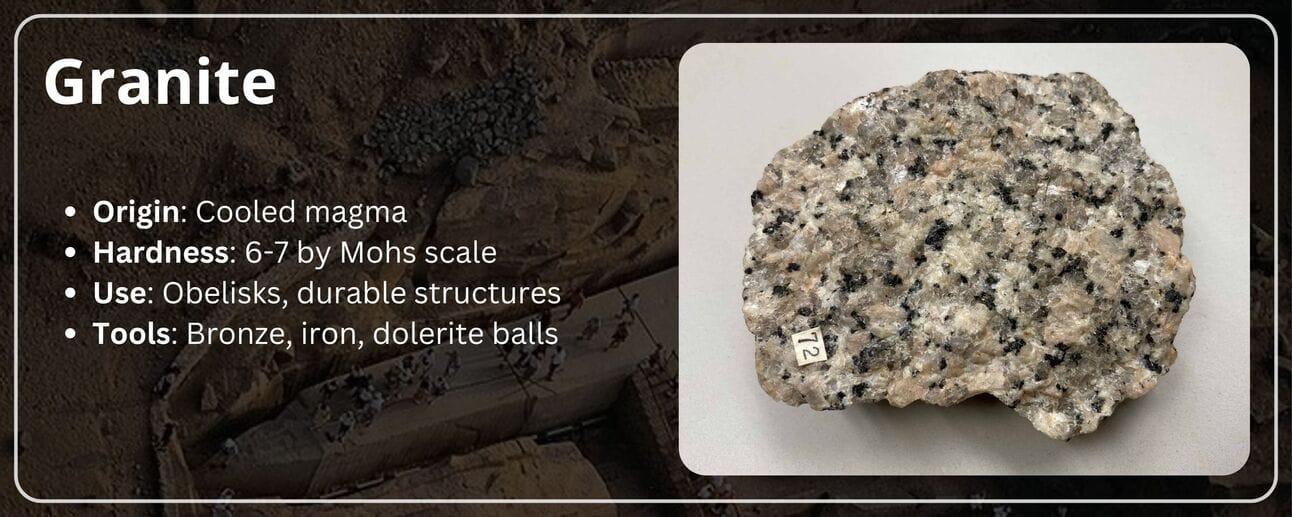

Granite

Granite Meta card

🟢 Origin: A rock that forms when hot, melted rock (magma) cools down slowly deep underground, made mostly from minerals like quartz, feldspar, and mica.

🌋 Category: Igneous.

💪 Hardness: Hard, around 6 to 7 on the Mohs scale, making it durable but challenging to work with ancient tools.

⚒ Tools for Working: Required hard, durable tools like bronze or iron. Ancient Egyptians used dolerite balls for pounding.

🌦 Weathering: Very resistant to weathering, often used in outdoor structures that last for millennia.

🏗 Historical Use: Ancient Egyptians used it for obelisks and sarcophagi; also seen in Roman and medieval European buildings.

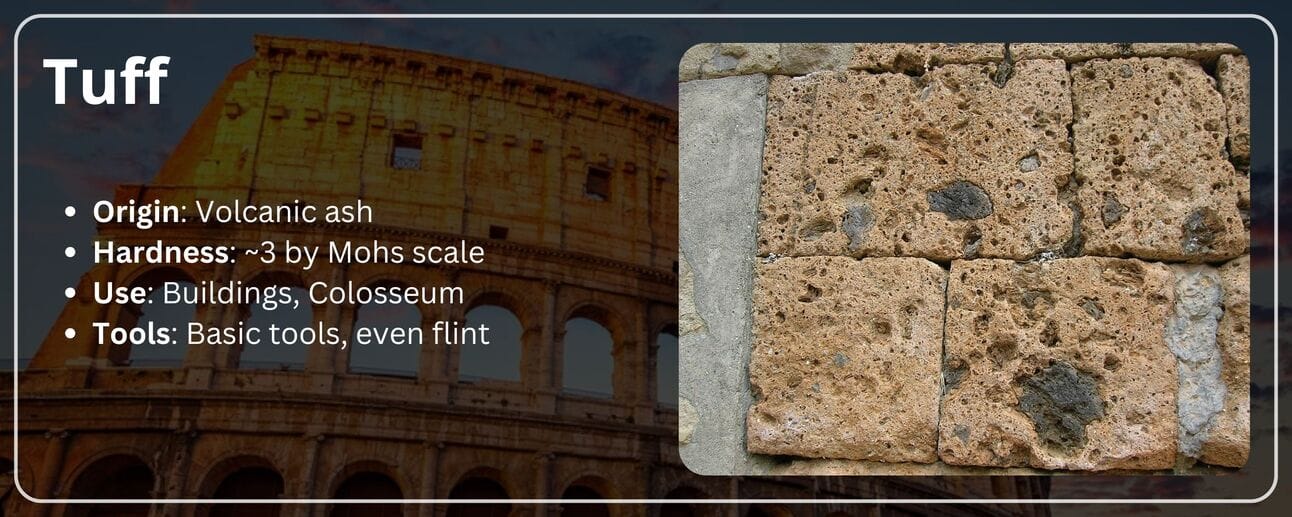

Tuff

Tuff Meta card

🟢 Origin: A type of rock made up of volcanic ash compressed into a solid rock.

🪨 Category: Sedimentary.

💪 Hardness: Variable, but generally softer, around 3 on the Mohs scale when fresh.

⚒ Tools for Working: Easily worked with basic tools, even flint, due to its initial softness.

🌦 Weathering: Can harden over time but still susceptible to erosion.

🏗 Historical Use: Romans used it extensively, especially in Pompeii and for building the Colosseum's upper levels.

Decorative and Artistic Stones

Aesthetically pleasing, often used to convey wealth, power, or cultural significance.

Marble

Marble Meta card

🟢 Origin: A type of rock that's made when limestone gets transformed under heat and pressure, turning into a beautiful, shiny stone made mostly from minerals like calcite or dolomite.

🔄 Category: Metamorphic.

💪 Hardness: Around 3 to 4 on the Mohs scale, similar to its parent rock, limestone, but with a more crystalline structure.

⚒ Tools for Working: Can be carved with metal tools; ancient Greeks and Romans used iron chisels for fine work.

🌦 Weathering: Less soluble than limestone but can still weather due to acid rain. Marble surfaces can dull over time.

🏗 Historical Use: Valued for its beauty, used in Greek and Roman sculptures, architectural elements in buildings like the Parthenon and Pantheon.

Alabaster

Alabaster Meta card

🟢 Origin: A smooth, fine rock made mostly from gypsum or calcite, perfect for carving because it's so soft.

🪨 Category: Sedimentary.

💪 Hardness: Very soft, 1.5 to 2 on the Mohs scale for gypsum alabaster, making it easy to carve with simple tools.

⚒ Tools for Working: Could be worked with flint or even wood tools for basic shaping.

🌦 Weathering: Sensitive to moisture, can erode in humid environments.

🏗 Historical Use: Prized by Egyptians for sculptures, vessels, and tombs; also used in Assyrian and Roman art.

Diorite

Diorite Meta card

🟢 Origin: A rock that forms when magma cools down, with a mix of common minerals (plagioclase feldspar and hornblende) that give it a unique texture, somewhere between granite and basalt.

🌋 Category: Igneous.

💪 Hardness: Around 6 to 7 on the Mohs scale, similar to granite, making it tough to work.

⚒ Tools for Working: Needed durable tools like bronze or iron; often used in its natural form due to hardness.

🌦 Weathering: Very resistant, used for long-lasting structures.

🏗 Historical Use: Famous for the Code of Hammurabi, also used by Egyptians for statues and monuments.

Utility Stones

Everyday or specific functional needs, from durable road surfaces to practical household items.

Basalt

Basalt Meta card

🟢 Origin: A little brother to Granite, rock that forms when hot, flowing lava cools down quickly, packed with minerals like iron and magnesium.

🌋 Category: Igneous.

💪 Hardness: Generally 5 to 6 on the Mohs scale, harder than many sedimentary rocks but less than granite.

⚒ Tools for Working: Worked with bronze or iron tools, though it was often used in its natural state due to hardness.

🌦 Weathering: Can weather to form rich, fertile soils but is generally resistant to erosion.

🏗 Historical Use: Used by many ancient cultures for tools, statues, and constructions like the Roman roads or the Giant's Causeway in Ireland.

Slate

Slate Meta card

🟢 Origin: A rock that starts as mud or clay, gets squeezed and heated deep underground, turning into thin, layered sheets with shiny bits mixed in.

🔄 Category: Metamorphic.

💪 Hardness: About 2.5 to 4 on the Mohs scale, making it relatively soft for a metamorphic rock.

⚒ Tools for Working: Can be split easily along its cleavage planes with simple tools.

🌦 Weathering: Resistant to weathering, often used for roofing due to its durability against elements.

🏗 Historical Use: Used for writing surfaces, tombstones, and roofing since ancient times.

Soapstone (Steatite)

Soapstone Meta card

🟢 Origin: A rock composed mostly of talc, which gives it its characteristic softness and soapy feel.

🔄 Category: Metamorphic.

💪 Hardness: Very soft, around 1 on the Mohs scale, making it one of the easiest minerals to carve.

⚒ Tools for Working: Can be shaped with basic tools, even wood or bone in ancient times.

🌦 Weathering: Resistant to heat and acid, used for cooking utensils, but can wear over time.

🏗Historical Use: Popular for carvings, vessels, and tools in many ancient cultures due to its workability and heat resistance.

Specialized Stones

Stones that had unique characteristics making them suitable for niche applications in building. Yes, I really had to make this special case for just a single rock.

Schist

Schist Meta card

🟢 Origin: A rock that changes shape under the Earth's squeeze, turning into layers full of shiny mica, due to lots of pressure.

🔄 Category: Metamorphic.

💪 Hardness: Variable, but generally around 4 to 5 on the Mohs scale, influenced by its mineral composition.

⚒ Tools for Working: Requires metal tools for effective shaping due to its toughness.

🌦 Weathering: Can flake or split along foliation planes, making it less durable for some applications.

🏗 Historical Use: Less common in fine art but used in construction where its layered nature was beneficial or decorative.

What is The Mohs scale anyway

There are references to mysterious "Mohs scale" and I haven’t told you anything about it yet. Well, I bet you already figured out it has something to do with evaluation of how hard the stone is, so let's deepen this understanding of this actually handy yet simple concept:

Mohs hardness scale, or simply Mohs scale, is a relative ranking from 1 to 100 that compares how easily one mineral can scratch another. Devised in 1812 by German mineralogist Friedrich Mohs.

Basic principle: if mineral A can scratch mineral B, then mineral A is harder, otherwise it is softer.

Think of “Rock paper scissors” game but rocks-only edition!

Better luck next time

Mohs scale devised specifically for quick and rough evaluation in the fields - there are other hardness tests, but they won't help you outside of lab.

Here, take a look at a more proper visualization:

Yes, there is a fingernail mentioned, don't be surprised!

Stone Categories Explained

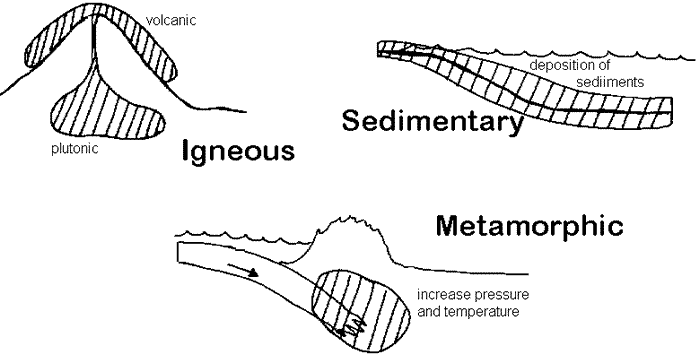

When we talk about the stones ancient civilizations used, it's like looking at a rock family tree. There are three main branches:

Sedimentary Stones: Imagine tiny bits of sand, shells, or mud settling down at the bottom of a river, lake, or ocean. Over millions of years, these layers get squashed together under pressure. That's how you get sedimentary rocks like limestone or sandstone. They're like the history books of geology because they often have fossils or layers telling us about the past environments.

Metamorphic Stones: Now, think of these as the rocks that went through a rock makeover. They start as one type of rock, but then heat and pressure from deep within the Earth change them. It's like a caterpillar turning into a butterfly. Marble, for example, starts as limestone but gets all fancy with swirls and patterns after this transformation.

Igneous Stones: These are the rock rebels - born from the fiery insides of the Earth. When magma cools down, either deep underground or after a volcanic eruption on the surface, you get igneous rocks. Granite forms deep below, taking its cool time to crystallize, while basalt is like the quick-cool kid on the block, forming from lava that chills fast at the surface.

Each type has its own character and use:

Sedimentary - Great for carving and construction where you need to shape the rock easily.

Metamorphic - Often chosen for beauty in sculptures or building exteriors because of their unique patterns.

Igneous - Valued for durability; think of structures that need to stand the test of time or withstand heavy use.

Thus understanding these categories helps us appreciate not just what ancient builders had to work with but also how these choices shaped (pun intended) their architecture, art, and even daily life.

Now what

Hope you haven’t just skimmed all the way down here

Your head is full of stones now and it isn't just for the trivia buffs; it's your key to unlocking the narrative of human history. Each stone tells a tale of the geological processes, the technological prowess, and the cultural priorities of the time. Knowing whether a structure is made from limestone, granite, or basalt can tell you about the tools available, the skill of the artisans, and even the economic resources of the civilization.

When you're standing before a mysterious structure in the middle of nowhere, the stones themselves become your guide. Here’s how:

Color and Texture: These can indicate the stone type. For instance, the warm yellows and reds of sandstone suggest a different geological story than the cool grays of granite.

Shape and Layout: The way stones are cut or laid can reflect the era's construction techniques. Perfectly aligned blocks might point to advanced tools or methods.

Erosion: The degree and type of weathering on the stones can reveal how long they've been exposed to the elements. Limestone might show dissolution patterns, while granite could exhibit surface cracks.

Tracks of Tools: Look for marks left by the tools used to shape the stone. Rough, uneven marks might suggest simpler tools like flint or bronze, while smoother, more precise cuts could indicate the use of iron tools, hinting at the time period of construction.

I am not certified Indiana Jones yet, but got opportunity to test the knowledge. Here is one case on top of the head: recently I was lucky to have visited Carthage's famous Antonine baths. It happened so that I made no specific preparation for the place, and an architectural salad there got me by surprise.

Nevertheless, I was able to get pretty good grasp on what happened there:

Massive sandstone blocks serving as foundation. Quarried locally - sheer size and volume leaves no question whether it makes sense to transport this from anywhere

Opus cameneticium, or Roman concrete, was used apparently to construct the part right above the foundation, and in some places substituted sandstone

Marble remains of pillars bodies, friezes, capitels - had to be imported from somewhere, as there are no sources of marble in North Africa

…and so on, I hope you get the point.

History isn't an exact science; it's more like a tapestry with some threads missing. The stories we tell are interpretations based on the evidence we have.

What's taught as fact can change with new discoveries. Sites can be misidentified, or the narrative might be incomplete. Places like Carthage are perfect examples where you'll find structures from various epochs side by side. You might see Punic stones next to Roman bricks, all telling different chapters of the same city's story.

Isn't it thrilling then to try to piece together these clues yourself?..

Congratulations! 👏

You made it - now you are ahead of 99% of population on this topic, if not more. To better remember, teach somebody else on the basics. Here is a handy picture with all the stone cards for your quick reference:

Stones cheat sheet

I'd like to mention a little caveat though: this list doesn't include man-made stones like the antique concrete heavily employed by the Romans, clay bricks from Mesopotamia, or plaster. There's plenty to say on these topics, so perhaps a Part 2 will follow. For now, if a structure's composition doesn't look naturally formed, it's probably man-made!

Don't forget to apply the knowledge in practice in your next trip to the cradle of civilizations, Mediterranean region, or whatever really that sparks your interest for the stone is the only truly universal material out there.

Remember, now when you visit ancient sites, you're not just a tourist; you're a historical detective on an adventure, and every stone is a clue waiting to be interpreted.

I am Rick, and I write pieces on Ancient History and related topics as I progress towards my PhD in 10 years starting from zero 🚀

If you liked what you read, follow me for more pieces on X, Threads, and sign up right at the bottom of this page to my occasional newsletter - zero fee, ads-free, pure curiosity driven 😉